Celebrating Black History Month as a Community

Earlier this month, President Greg Weiner asked the Assumption community to share and reflect on the lessons they have taught and learned about the contributions of Black thinkers, authors, scientists, historical figures, and citizens who have shaped our shared historical and intellectual experience. Here are some of the responses from the community:

John Bell, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of History: “The African American Dream”

Because African American history is American history, it features in every class I teach as one of Assumption’s U.S. history faculty. But one of my courses is specifically focused on Black history, HIS 269: The African American Dream. This class asks how the Black freedom struggle fits into the larger American democratic experiment. Its central theme is the longstanding tension in African American culture between racial integration and racial self-determination.

As a historically oppressed minority, African Americans have perennially grappled with the question of whether to define themselves as part of or apart from American society. The course begins in the late nineteenth century, after African Americans had received the full rights of citizenship during Reconstruction only to see those rights taken away under Jim Crow. The nation’s failure to live up to the ideal of liberty and justice for all left Black citizens in a quandary. Should they seek full access to a majority white society which had scorned them? Or should they pursue their own separate course and risk reinforcing the logic of racial segregation? Which of these paths would best affirm their equal dignity and honor their full personhood?

The syllabus features primary texts in which generations of Black intellectuals and activists—from Ida B. Wells to Angela Davis, Booker T. Washington to Barack Obama—responded to this dilemma. The goal is not to prove whose approach was best or right. Instead, it is to discern why these figures thought the way they did given their ideals, identities, and circumstances. In turn, we consider how these same factors shape our own points of view.

Studying the history of one minority and debates within that community over its relationship to the majority can help students of all backgrounds understand how race and racism have shaped American society. While the struggle of African Americans is historically and culturally specific, the quest for freedom implicates all people. As the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer famously said, “nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Savina Villani, Class of 2027 – Poem: “Doesn’t Exist”

Racism doesn’t exist.

Not in America.

Not in a country

that was founded by great Fathers.

Not in a country

with equality as its staple, its bond.

Not in a country

where all men are created equal.

“All men,”

while black men

broke their backs then,

and back then

hear the crack, and

they were broken,

their wounds open,

burning canyons

bleeding hope, and

America broke them.

Then came

the laws enforcing slavery,

the flaws announcing inferiority

the lie was planted, they

let it grow,

let modernity see

disproportionality.

And with it,

financed prosperity,

And with it,

advanced inequality.

But no.

Racism doesn’t exist.

Not in a country

that was made for others to be owned.

Not in a country

with slavery as its cornerstone.

Not in a country

With segregation,

Not in a nation

Full of hate and

Disgrace,

Targeted towards

The black race.

There are people that are

Broken,

Battered.

Taken,

Tattered.

Shaken,

Shattered,

But what’s sadder

Is that it never mattered.

That it was

too uncomfortable

to be confront-able.

That it lay before our eyes

But we failed to recognize the

Centuries of lies the

Senseless ways we let it rise.

No.

Racism shouldn’t exist.

And we

can change that.

Gennifer Dorgan, Adjunct Professor of Modern and Classical Languages

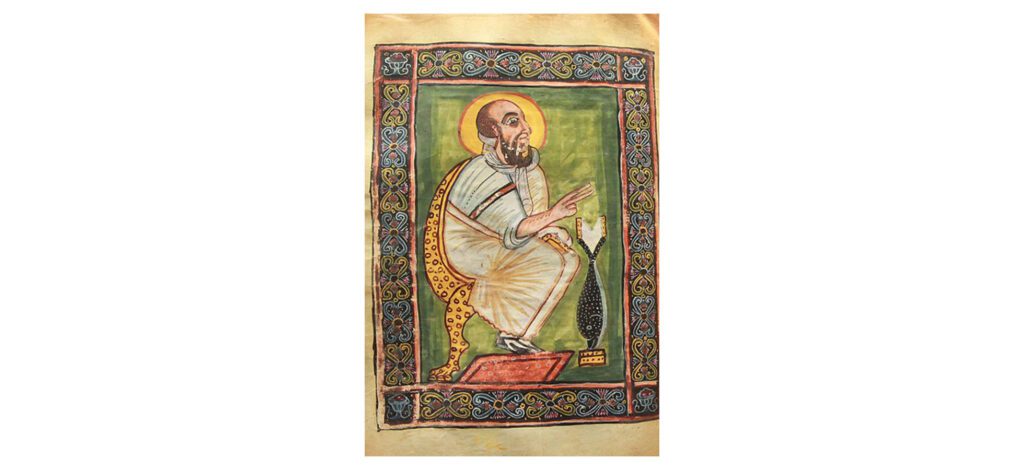

In my Latin courses at Assumption, I’ve taught my students about the medieval Latin manuscript traditions that (in many respects) began in Ireland, where famous illuminated Gospel books like the Lindisfarne Gospels were produced in the 8th century AD. The D’Alzon Library has a stunning collection of medieval Latin manuscript leaves! However, I always find it important to share with my students that these early Latin gospel books were preceded by the Abba Garima Gospels, produced in the Aksumite Empire (present-day Ethiopia) c. 530-630 AD. This manuscript is the first fruit of a tradition that began in northern Africa when the Gospels were translated from Greek into Ge’ez in the 5th century. See this beautiful portrait of Mark the Evangelist:

Most people don’t realize that the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church – the same institution that produced the Garima Gospels in late antiquity – is an indigenous African church with ancient traditions that continue to thrive.

Anita Danker, Ph.D., Adjunct Professor of Education: “Meta Warrick Fuller: Artist and Activist (1877 – 1968)”

A striking example of public art in Boston’s South End is the bronze statue Emancipation in Harriet Tubman Park. Meta Warrick Fuller, an African American artist and activist, who lived most of her adult life in Framingham, Massachusetts, created the work, which was first displayed at the National Emancipation Exposition in New York City in 1913. Commissioned to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, it is a somber piece, designed to raise questions and promote reflection.

The artist was born Meta Vaux Warrick in 1877 to parents who were members of Philadelphia’s prosperous black middle class. The couple introduced their children to the many cultural experiences the city had to offer. Meta studied art, music, and dance. She earned a scholarship to attend art school and, upon graduation, was awarded funds for additional study. She decided to go to Paris.

Meta’s time in France did not begin well when she was denied lodging at the American Girls’ Club because of her race. Refusing to be discouraged, she studied sculpture and was introduced to W.E.B. Du Bois, who became her friend and supporter. One of her exhibits attracted the attention of Auguste Rodin who became her mentor. Her 1902 piece The Wretched earned her the nickname “delicate sculptor of horrors.”

Despite her success in Europe, back home Meta found that her work did not sell well. She accepted a commission from the federal government to create a display for the Jamestown Tercentennial Exhibition (1907). Her diorama depicting the progress of African Americans received a gold medal.

In 1909, Meta married Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, a pioneer in the study of Alzheimer’s disease. The newlyweds moved to Framingham where initially they were not welcomed into the neighborhood. Over time, however, the Fullers became admired members of the community. They raised three sons and entertained distinguished guests in their home. When Meta’s Paris artwork was destroyed in a fire, she arranged for a new studio to be built on the Framingham property.

Struggling with the demands of family and career, Meta nonetheless continued her creative work. She is now considered to be a precursor of the Harlem Renaissance. Her sculpture addresses themes of religion, family, African heritage, and the black experience in America. She dedicated a wrenching statuette to Mary Turner, a young black woman brutally murdered by a white mob after she threatened to press charges against those who had lynched her husband.

Meta Fuller joined the Framingham Equal Suffrage League and designed a medallion to raise funds for the cause. She became a member of the state branch of the Women’s Peace Party, protested the showing of The Birth of a Nation, and was awarded a citation of merit by the Boston Chapter of the NAACP.

The Danforth Art Museum in Framingham houses a room dedicated to Fuller’s artwork and includes a replica of her studio. The Fuller Middle School was named in honor of the family.

Carl Keyes, Ph.D., Professor of History

Greg Weiner, Ph.D., President of Assumption University

Political Science courses at Assumption regularly include theorists ranging from, among others, W.E.B. DuBois, a profound educational thinker, to Martin Luther King Jr., whose leadership of the civil rights movement was deeply rooted in theology and political theory.

I’ve often taught King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which occurred at a landmark moment in history and is also a landmark of 20th century American political thought, alongside Abraham Lincoln’s 1838 lecture “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” Lincoln’s lecture makes the case for the necessity of obeying laws, while King argues that breaking an unjust law can be a lawful act. That pairing raises deep questions. Can those views be reconciled? Does a republic need voices of both governing and protest? And so forth.

When I teach King’s letter, I ask students a question we should ask one another and ourselves during Black History Month. King spent eight days in jail in April 1963. How much would it disrupt any of our lives today to spend even two or three days in jail?

For most of us, the disruption in time alone would be immense, to say nothing of the conditions under which King was held. He was arrested on April 12, Good Friday, and released eight days later only under intense pressure from national authorities. King paid a far higher price, of course, in 1968. Those eight days in April 1963 also remind us that justice requires sacrifices so deep many of us cannot comprehend them. All of us, amid the relative comfort of our daily lives, need to be willing to make more of them.

We have work to do to make Assumption an institution where everyone—regardless of who they are or what they believe—has a home. We also have the advantage of the example King—and so many other figures in Black History, both celebrated and lesser known—have set for us.

This article will continue to be added to as submissions from the Assumption community are received. If you would like to submit a piece, please contact acpa@assumption.edu.